A GUIDE FOR PARENTS ON

Talking to Kids about Asian American Identity & Racism

Made possible with funding from CT Humanities & Graustein Memorial Fund.

Access this guide in different languages:

中文 (Chinese)

Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

한국어 (Korean)

हिंदी (Hindi)

Tagalog (Tagalog)

नेपाली (Nepali)

中文 (Chinese)

Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

한국어 (Korean)

हिंदी (Hindi)

Tagalog (Tagalog)

नेपाली (Nepali)

Since the start of the COVID-19 crisis, racially-motivated attacks have targeted Asian Americans and Asian communities across the globe. Asian American children have also faced increased incidence of racialized bullying connected to COVID. In order to fully understand the current moment and the surge in anti-Asian violence, we must delve deeper into Asian American identity, the origins of anti-Asian racism, and conduct conversations with kids with trauma-informed approaches.

The Immigrant History Initiative, in partnership with Parents for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion of West Hartford, CT, and Dr. Jenny Wang, developed a workshop on talking to kids about Asian American identity and racism. This guide reflects the conversations of that workshop and contains additional tools to guide parents and other adults in having conversations with kids about their own identity and understanding the complex dimensions of racism.

1800-1930s: The First Asian Americans

Asian Americans have a long history in America. The earliest record of Asians in the Americas dates back to the 1500s! The first Asian American communities were established in the 1800s, around the same time as mass immigration occurred from Western and Northern Europe.

The first big wave of Asian migration to the U.S. took place in the late 1800s, mostly to meet labor needs in the country. Thousands of Chinese men were recruited to work on building the railroads on the West Coast and hired as miners during the Gold Rush. Japanese and Korean laborers were recruited to Hawaii to work on sugar plantations.

South Asian men from the Punjab and Bengali regions came to the U.S. and worked in mills, farms, and railroads. Many were already in the Caribbean British colonies as indentured laborers. After the Philippines became a colony in 1898, Filipinos were recruited first as students and soon after as agricultural laborers in Hawaii and on the mainland.

What was life like?

Life was very hard for most Asian immigrants. They faced discrimination, violence, and serious financial difficulties. Because many were brought to America by their employers, they often spent years working to pay off “debts” before being able to make money. They were paid less than white workers and worked the most dangerous jobs.

Even though Asian immigrants made up a small percentage of the total number of U.S. immigrants, their presence was met with violence and exclusion. Western states passed laws that restricted where Asians could live and who they could marry. Anti-Asian riots were common in the late 1800s and early 1900s, where white mobs killed many and drove entire Asian communities out of town.

In 1882, after decades of anti-Chinese sentiment, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first immigration law to prohibit immigration of an ethnicity or race. It also prevented any Chinese immigrant from gaining U.S. citizenship. This law was only the beginning of a string of increasingly restrictive anti-Asian Immigration laws.

The first big wave of Asian migration to the U.S. took place in the late 1800s, mostly to meet labor needs in the country. Thousands of Chinese men were recruited to work on building the railroads on the West Coast and hired as miners during the Gold Rush. Japanese and Korean laborers were recruited to Hawaii to work on sugar plantations.

South Asian men from the Punjab and Bengali regions came to the U.S. and worked in mills, farms, and railroads. Many were already in the Caribbean British colonies as indentured laborers. After the Philippines became a colony in 1898, Filipinos were recruited first as students and soon after as agricultural laborers in Hawaii and on the mainland.

What was life like?

Life was very hard for most Asian immigrants. They faced discrimination, violence, and serious financial difficulties. Because many were brought to America by their employers, they often spent years working to pay off “debts” before being able to make money. They were paid less than white workers and worked the most dangerous jobs.

Even though Asian immigrants made up a small percentage of the total number of U.S. immigrants, their presence was met with violence and exclusion. Western states passed laws that restricted where Asians could live and who they could marry. Anti-Asian riots were common in the late 1800s and early 1900s, where white mobs killed many and drove entire Asian communities out of town.

In 1882, after decades of anti-Chinese sentiment, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first immigration law to prohibit immigration of an ethnicity or race. It also prevented any Chinese immigrant from gaining U.S. citizenship. This law was only the beginning of a string of increasingly restrictive anti-Asian Immigration laws.

|

In 1907, the U.S. signed the Gentleman’s Agreement to limit Japanese immigration. In 1917, the Asiatic Barred Zone Act was passed to prohibit almost all immigration from the Middle East to Southeast Asia. Finally, the 1924 Immigration Act, which set up quotas for non-Western European immigrants, prohibited all immigration from Asia.

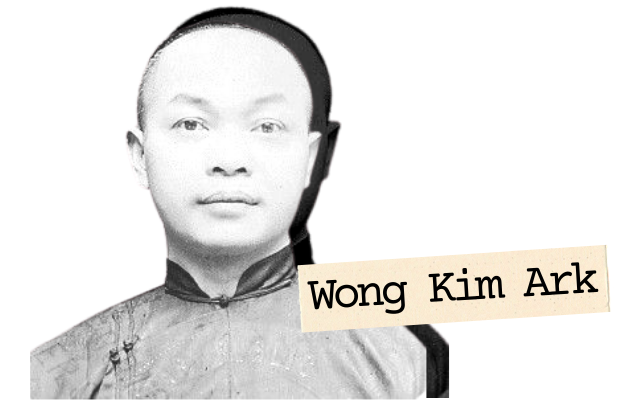

From the beginning, Asian Americans reacted to mistreatment by fighting for their rights. Their fights led to the establishment of important American principles. For example, an 18-year old Chinese American named Wong Kim Ark challenged the government’s refusal to recognize him as a citizen even though he was born there. His fight established that everyone born in the U.S. is an American citizen. |

1940s - 1960s: A New Generation

In the early 20th century, a new generation of Asian Americans emerged. During WWII, Asian Americans served in large numbers in the war effort, even as Japanese Americans were imprisoned in internment camps because of their ethnicity and questioned about their loyalty to the U.S.

Asian Americans continued to fight for equality and justice. Fred Korematsu challenged Japanese Internment in the courts, and the No-No Boys refused to join military service as protest against the imprisonment of Japanese Americans in the camps. To combat labor exploitation, Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, and other Filipino workers organized the Delano Grape Strike with Cesar Chavez and Mexican laborers and started the United Farm Workers Union.

The population of Asian Americans also grew after WWII. By 1952, Chinese Exclusion was repealed, and the law changed to allow naturalization of non-white immigrants, paving the way for Asian immigrants to become citizens. The U.S. also began an Exchange Program bringing small numbers of professionals and skilled workers from Asia, including a number of Filipina nurses.

Asian Americans continued to fight for equality and justice. Fred Korematsu challenged Japanese Internment in the courts, and the No-No Boys refused to join military service as protest against the imprisonment of Japanese Americans in the camps. To combat labor exploitation, Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, and other Filipino workers organized the Delano Grape Strike with Cesar Chavez and Mexican laborers and started the United Farm Workers Union.

The population of Asian Americans also grew after WWII. By 1952, Chinese Exclusion was repealed, and the law changed to allow naturalization of non-white immigrants, paving the way for Asian immigrants to become citizens. The U.S. also began an Exchange Program bringing small numbers of professionals and skilled workers from Asia, including a number of Filipina nurses.

1950s - 1970s: Becoming Asian American

During the 1960s, Asian Americans actively participated in struggles for justice with other communities. They participated in the civil rights movement, women’s liberation, and protests against the Vietnam War. For example, Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama worked extensively with Black leaders during the Civil Rights Movement. Patsy Mink, the first Asian American woman elected in Congress in 1956, advocated for women’s equality and children’s rights.

Civil rights activists also called for immigration reform, pointing out the racist roots of the immigration laws. Their advocacy led to the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. This Act ended previous eras of exclusion based on racial categories and instituted a new system that is based on employment, family reunification, and refugee claims. The Act led to significant increases in immigration from Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

Civil rights activists also called for immigration reform, pointing out the racist roots of the immigration laws. Their advocacy led to the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. This Act ended previous eras of exclusion based on racial categories and instituted a new system that is based on employment, family reunification, and refugee claims. The Act led to significant increases in immigration from Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

|

Asian American identity, and the Yellow Power movement, was formed through activism and inspired by other social movements: civil rights, the Black Power movement, and anti-war protests. Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee founded the Asian American Political Alliance in 1968 at Berkeley and inspired similar organizations from New York to Hawaii. Asian, African American, Chicano, and Native American students joined together in the Third World Liberation Front to demand educational programs that focused on the history and experiences of people of color.

|

1970s - Present: Growing Communities

Between 1975 and 2010, 1.2 million Vietnamese, Lao, Hmong, and Cambodian peoples came to America, many of them refugees. Initial efforts to admit refugees in the late 1970s led to anti-immigrant backlash, including violence and exclusion in their new homes. The public debate led to the passage of the Refugee Act of 1980, which created restrictions on the number of refugees and controlled geographic relocation. Nevertheless, strong Southeast Asian communities formed, such as the Hmong community in Minnesota.

During the 1980s, 7.34 million immigrants came to the U.S., over 80% from Asia and Latin America. The 1965 Act emphasized admitting educated professionals, and many immigrants from Asia came as workers to meet the demands of the booming technology and medical industries in the US.

Today, Asian Americans make up the fastest growing demographic in the voting population and enjoy increasing political power and public presence. This history tells us that Asian Americans have never been silent in the fight for equality and justice. New generations of Asian Americans continue to call for greater representation, engagement with community issues, and for solidarity in confronting racism.

During the 1980s, 7.34 million immigrants came to the U.S., over 80% from Asia and Latin America. The 1965 Act emphasized admitting educated professionals, and many immigrants from Asia came as workers to meet the demands of the booming technology and medical industries in the US.

Today, Asian Americans make up the fastest growing demographic in the voting population and enjoy increasing political power and public presence. This history tells us that Asian Americans have never been silent in the fight for equality and justice. New generations of Asian Americans continue to call for greater representation, engagement with community issues, and for solidarity in confronting racism.

PREJUDICE: A negative belief or attitude toward someone or a group of people, typically based on unsupported generalizations or stereotypes.

DISCRIMINATION: When prejudice turns into action. Unequal treatment based on race, gender, social class, sexual orientation, ability, religion and other categories.

RACISM: The combination of racial prejudice and power. Racism is a complex system of individual and institutional beliefs and behaviors, based on the assumption that whiteness is superior. It results in the oppression of people of color and benefits the dominant group, whites.

MICROAGGRESSION: Individual experiences with racism, such as what a child might face at school. Microaggressions are verbal or nonverbal slights or insults and can be intentional or not. They communicate negative messages targeting persons based on race, etc.

STEREOTYPE: a widely held idea about a group of people based on an exaggerated or oversimplified generalization

DISCRIMINATION: When prejudice turns into action. Unequal treatment based on race, gender, social class, sexual orientation, ability, religion and other categories.

RACISM: The combination of racial prejudice and power. Racism is a complex system of individual and institutional beliefs and behaviors, based on the assumption that whiteness is superior. It results in the oppression of people of color and benefits the dominant group, whites.

MICROAGGRESSION: Individual experiences with racism, such as what a child might face at school. Microaggressions are verbal or nonverbal slights or insults and can be intentional or not. They communicate negative messages targeting persons based on race, etc.

STEREOTYPE: a widely held idea about a group of people based on an exaggerated or oversimplified generalization

Stereotypes Targeted at Asian Americans

Perpetual Foreigner

The “Perpetual Foreigner” stereotype is the assumption that all Asian people must be from outside the United States, or foreign. Examples: An Asian American gets asked “Where are you really from,” when he says that he is American, or an Asian American woman is told to "go back to your country" and assumed to have COVID-19 because she came from China.

This stereotype implies that Asians are never seen as a part of U.S. identity, which is often defined as Western European origin. It has manifested in violent ways, because when you are seen as un-American, you may also be seen as dangerous, disloyal, and immoral. Examples include the incarceration of all Japanese Americans during WWII for fear they were spies, the islamophobia and hate crimes against those who identify as South Asian, Muslim, or brown post 9-11, and most recently, the hateful rhetoric and angry attacks on Asians during COVID-19 pandemic.

Model Minority

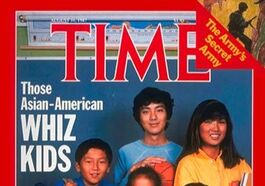

This myth is the belief that all Asians are successful, quiet, and obedient. At face value, it might feel like a “positive” stereotype. But the myth has ugly roots and has led to harmful consequences.

First, the idea that Asians are “docile” and “quiet” goes back to the 1800s. Asian men were seen as less “masculine” and described as more feminine. Asian immigrants were also silenced: they could not vote, they were heavily discriminated against, and their survival often depended on employers because of their immigration status.

The “Perpetual Foreigner” stereotype is the assumption that all Asian people must be from outside the United States, or foreign. Examples: An Asian American gets asked “Where are you really from,” when he says that he is American, or an Asian American woman is told to "go back to your country" and assumed to have COVID-19 because she came from China.

This stereotype implies that Asians are never seen as a part of U.S. identity, which is often defined as Western European origin. It has manifested in violent ways, because when you are seen as un-American, you may also be seen as dangerous, disloyal, and immoral. Examples include the incarceration of all Japanese Americans during WWII for fear they were spies, the islamophobia and hate crimes against those who identify as South Asian, Muslim, or brown post 9-11, and most recently, the hateful rhetoric and angry attacks on Asians during COVID-19 pandemic.

Model Minority

This myth is the belief that all Asians are successful, quiet, and obedient. At face value, it might feel like a “positive” stereotype. But the myth has ugly roots and has led to harmful consequences.

First, the idea that Asians are “docile” and “quiet” goes back to the 1800s. Asian men were seen as less “masculine” and described as more feminine. Asian immigrants were also silenced: they could not vote, they were heavily discriminated against, and their survival often depended on employers because of their immigration status.

|

In the 1950s and 60s, the image of Asian Americans changed with new immigration laws that admitted Asian immigrants to fulfill needs for technical and medical positions. Asians were described as financially successful and quiet as a way to criticize the protests and struggles of the Civil Rights Movement. The model minority myth originated as a weapon against other people of color and continues to be used to deny funding and services and to over-police other communities of color.

|

The model minority myth also seriously hurts Asian Americans. It makes the needs of Asian Americans invisible and erases the diversity of the Asian American community. The model minority is seen as entirely upper-middle class and “doesn’t need help,” so resources and services are not allocated to Asian American communities proportionally. When Asian children are bullied, teachers often don't recognize it as racist, and try to sweep it under the rug. The myth also works to keep Asian Americans from getting leadership positions, because they are often dismissed as too quiet and compliant.

Ideally, you and your child have already begun discussing race at home through books, age-appropriate resources, and conversations around the idea that people sometimes use visible attributes to judge others. In addition, you have been sharing your cultural background with your child through actions like learning languages, sharing stories about your homeland, and exploring rituals, foods, and other aspects of your ethnic heritage.

Even if you have been taking steps to share your cultural and racial background, when your child encounters a racialized incident or racist interaction, your first reaction may still be shock and outrage. These events are frightening, for both child and parent, and you may feel unable to fully understand what happened or at a loss for how to help your child grapple with the incident.

This guide aims to provide easy-to-follow steps to help you and your child navigate this intimidating process with empathy, self-care, and patience. You can use the below four steps as a starting point to guide your response.

Even if you have been taking steps to share your cultural and racial background, when your child encounters a racialized incident or racist interaction, your first reaction may still be shock and outrage. These events are frightening, for both child and parent, and you may feel unable to fully understand what happened or at a loss for how to help your child grapple with the incident.

This guide aims to provide easy-to-follow steps to help you and your child navigate this intimidating process with empathy, self-care, and patience. You can use the below four steps as a starting point to guide your response.

|

Step 1: Emotional & Physical Regulation

One of the most important messages a child can receive after a racialized event is that the child is safe. If your child is upset by this incident, give them ample time to feel and process their emotions. Encouraging different forms of emotional expression may be helpful such as journaling, drawing, painting, dancing, playing music, etc. Sometimes these topics may be too confrontational to discuss directly, so having these discussions while working on a puzzle, going for a walk, etc., can diffuse some of the intensity. |

|

Step 2: Investigation

Become a detective with your child. Walk through what happened and how it made them feel. Be curious about the circumstances. Brainstorm alternative possibilities or reasons for why someone behaved in a racialized way towards them. Do not jump to shame or judgment, even if your child may have been in the wrong or gotten into a fight; this period of time is about open reflection and curiosity. Do not move to this step until both you and your child have calmed down emotionally. You will know that your child has calmed down when they are no longer angry, sad, withdrawn, etc. Give them as much time as needed to regulate emotions. |

|

Step 3: Problem-Solving

Now turn towards the future. What next steps should you and/or your child take? How might your child want to show up differently the next time a racialized encounter occurs? Allow your child to take the lead and brainstorm. This step is an opportunity for your child to take back their agency and self-generate ideas about what they can do in the future. Do not censor your child and welcome all ideas, both positive or negative. Once you have a list of several options, go through each of them and encourage your child to think about the pros and cons. This narrowing-down process by the child engages them in the decision-making process and encourages them to systematically understand and evaluate their response options. During this process, important priorities are whether the action would preserve your child’s safety, dignity, and freedom. |

|

Step 4: Practice

Let’s practice! In the moment of a racialized incident, your child will be stressed out. Their mind may go blank, and their body may go into fight, flight or freeze mode. It will be much easier for them to remember and execute the planned action if you practice together beforehand in a safe space. Role play the selected response and see how the child feels about it. If it does not feel right, then try other selected responses. |

Hypothetical Scenario #1: In School

Your daughter, who is in middle school, comes home upset because someone made fun of her eyes calling her "Slanty eyes." She told the teacher, who said the boy probably didn't mean it and was "just teasing." You're not sure that your daughter understands the comment was racist, but she is clearly upset about it.

STEP 1: EMOTIONAL & PHYSICAL REGULATION

Reassure your child that she is safe and affirm the distress that she is feeling. Someone called her a bad name, and it is normal to be upset when someone attacks you. Make sure she knows that you are open and willing to discuss what happened. If possible, do not let your own emotions dictate this conversation; let your child take the lead even if you feel more upset than she seems. If she continues to be distressed, try a grounding activity, such as journaling, drawing, or playing music.

Reassure your child that she is safe and affirm the distress that she is feeling. Someone called her a bad name, and it is normal to be upset when someone attacks you. Make sure she knows that you are open and willing to discuss what happened. If possible, do not let your own emotions dictate this conversation; let your child take the lead even if you feel more upset than she seems. If she continues to be distressed, try a grounding activity, such as journaling, drawing, or playing music.

STEP 2: INVESTIGATION

At this stage, you want to discuss what happened and find out more details.

At this stage, you want to discuss what happened and find out more details.

|

Sample Script:

“I can see that you are extremely upset by what that classmate said to you. It is hard to know what motivated her to say this to you, but we do know that it is wrong. When I was your age, the same thing actually happened to me and I remember feeling very hurt as well. [Share about your own personal story with racial trauma as is age appropriate].” “People will sometimes hear mean things from other people and repeat them, but no one is born thinking this way. Our ancestors and Asian Americans throughout history have not been treated equally by all people. A lot of the time people are scared of things or people they are not familiar with. In your lifetime, many people will say all kinds of things to you and you will need to decide what kind of messages you allow inside. Just because someone says something about you does not make it true, and so we need to question the messages that come our way.” |

STEP 3: PROBLEM-SOLVING

Now that you have a clear sense of what happened, encourage your child to brainstorm ideas of next steps to take, or what she could have done in the moment. Allow your child to think of a full range of ideas, good or bad, and do not censor her even if the idea seems destructive.

Examples of good and bad possible ideas, ALL of which are acceptable for the child to brainstorm:

Once you have developed a list of possible reactions, now encourage the child to think about each option and decide whether this action is a good idea and if it preserves the child’s safety, dignity, and freedom. Support the child in deciding which option(s) they would like to practice in Stage 4.

Now that you have a clear sense of what happened, encourage your child to brainstorm ideas of next steps to take, or what she could have done in the moment. Allow your child to think of a full range of ideas, good or bad, and do not censor her even if the idea seems destructive.

Examples of good and bad possible ideas, ALL of which are acceptable for the child to brainstorm:

- Respond by identifying this statement as racist and asking the other person to stop.

- Leave the situation and report to the teacher.

- Talk to trusted friends about this situation and how they might be able to support the student if this encounter occurs again.

- Punch other student.

- Yell at other student.

Once you have developed a list of possible reactions, now encourage the child to think about each option and decide whether this action is a good idea and if it preserves the child’s safety, dignity, and freedom. Support the child in deciding which option(s) they would like to practice in Stage 4.

STEP 4: PRACTICE

Role play the selected options with your child and take time to debrief after each one. How does your child feel afterward? Is there anything she wanted to change? Keep moving through options until one of them feels right to her.

Role play the selected options with your child and take time to debrief after each one. How does your child feel afterward? Is there anything she wanted to change? Keep moving through options until one of them feels right to her.

What if...?

After talking to your child, you are considering speaking with the teacher about the situation. You are not sure how to proceed or how the teacher might respond.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS:

As a parent, you are responsible for the safety and protection of your child. However, we also want to empower our children when developmentally appropriate.

If you child is old enough to speak for themselves, you can begin by asking some questions:

Ideally, you want to empower your child to be part of the decision process on how they would like you to proceed. Then proceed with the plan in meeting with the teacher/school. Visit this link for email templates to teachers when this type of situation occurs.

As a parent, you are responsible for the safety and protection of your child. However, we also want to empower our children when developmentally appropriate.

If you child is old enough to speak for themselves, you can begin by asking some questions:

- What would you like to do in this situation?

- Would you like me to talk to your teacher further about this so they understand how this impacted you?

- Would you like to come with me or would you like me to do it without you present?

- Do you have any concerns about me discussing this with your teacher?

Ideally, you want to empower your child to be part of the decision process on how they would like you to proceed. Then proceed with the plan in meeting with the teacher/school. Visit this link for email templates to teachers when this type of situation occurs.

What if...?

You want to report this incident to the school, but your daughter really pushes back, stating that she is worried that the other kids will find out and tease her more.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS

You want to listen to your child. There may be aspects of this situation that you do not quite understand or your child has not shared them with you yet. Be open and patient with your child’s hesitance. Be curious and ask open ended questions:

Once you and your child have explored their resistance or hesitancy in more detail, it might be helpful to consider these following factors. Every child’s situation and school context is unique and will be impacted by different things. The decision about whether or not to report if the child feels uncomfortable with doing so is very complex. The below discussion only serves as a guide on the important factors you might consider as you make this difficult decision.

You want to listen to your child. There may be aspects of this situation that you do not quite understand or your child has not shared them with you yet. Be open and patient with your child’s hesitance. Be curious and ask open ended questions:

- Can you help me understand your worry that your classmates might tease you more?

- When does the teasing typically occur?

- What are the advantages or disadvantages of reporting this incident?

- What is the cost of not reporting this incident?

Once you and your child have explored their resistance or hesitancy in more detail, it might be helpful to consider these following factors. Every child’s situation and school context is unique and will be impacted by different things. The decision about whether or not to report if the child feels uncomfortable with doing so is very complex. The below discussion only serves as a guide on the important factors you might consider as you make this difficult decision.

Safety: If your child is unsafe (physically or psychologically) and you believe your child is unable to protect him/herself without intervention, potentially resulting in significant effects on physical and emotional health, then we must weigh the benefits and costs of not reporting. Children who are unable to feel physically or psychologically safe at school are at higher risk for mental health distress and psychological difficulties. Safety is the number one priority for our children.

Autonomy: It is also important that your child feels that they are a part of the decision-making process about whether they should report the incident. This decision-making process may not happen overnight. If your child continues to struggle with bullying or racism at school, it may be important to seek out help from a child and adolescent-focused mental health professional to help them develop coping skills, assertiveness, and confidence in these situations. It is possible that over time and through working with a mental health professional, the child may become more empowered and choose to report at a later time. Depending on the age of the child, autonomy becomes a larger piece of the decision making process. For example, a 6-year-old child will have different autonomy needs compared to a 15-year-old teenager.

School Support: Another consideration is whether your school has demonstrated awareness and accountability towards these issues. Some schools have a No Place for Hate designation (https://www.adl.org/who-we-are/our-organization/signature-programs/no-place-for-hate), which is a designation maintained by adhering to certain criteria in creating a school environment that is inclusive and safe for all students. These schools usually have curriculum taught by the school counselor about empathy, respect, kindness, and other prosocial skills to promote positive social interactions in school. If you believe that your school is committed to protecting vulnerable students during times of racism or bullying, it may give you more of a sense of safety in making a report. However, if your school does not appear to be committed to these ideals or you are uncertain, it may be worth discussing this further with your social support network, your child’s mental health counselor (if they have one), or even the child’s pediatrician to receive guidance on how to proceed.

Autonomy: It is also important that your child feels that they are a part of the decision-making process about whether they should report the incident. This decision-making process may not happen overnight. If your child continues to struggle with bullying or racism at school, it may be important to seek out help from a child and adolescent-focused mental health professional to help them develop coping skills, assertiveness, and confidence in these situations. It is possible that over time and through working with a mental health professional, the child may become more empowered and choose to report at a later time. Depending on the age of the child, autonomy becomes a larger piece of the decision making process. For example, a 6-year-old child will have different autonomy needs compared to a 15-year-old teenager.

School Support: Another consideration is whether your school has demonstrated awareness and accountability towards these issues. Some schools have a No Place for Hate designation (https://www.adl.org/who-we-are/our-organization/signature-programs/no-place-for-hate), which is a designation maintained by adhering to certain criteria in creating a school environment that is inclusive and safe for all students. These schools usually have curriculum taught by the school counselor about empathy, respect, kindness, and other prosocial skills to promote positive social interactions in school. If you believe that your school is committed to protecting vulnerable students during times of racism or bullying, it may give you more of a sense of safety in making a report. However, if your school does not appear to be committed to these ideals or you are uncertain, it may be worth discussing this further with your social support network, your child’s mental health counselor (if they have one), or even the child’s pediatrician to receive guidance on how to proceed.

Hypothetical Scenario #2: In Public

Your child is in high school. While grocery shopping, your child, you, and his grandfather run into a family friend, and the grandfather and friend start speaking in Hindi together while your child is listening. A white passerby glares at them, and says loudly to everyone in the store, "this is America, speak English." His grandfather and the friend look upset but don't say anything and stop talking.

STEPS 1 + 2: EMOTIONAL & PHYSICAL REGULATION + INVESTIGATION

When you are in a safe space, check in with your child about how he is feeling. In these situations where adults do not react, discuss, or process what happened during the incident, children are left to their own devices to make sense of the situation. We want to first assess how the child made sense of the situation.

When you are in a safe space, check in with your child about how he is feeling. In these situations where adults do not react, discuss, or process what happened during the incident, children are left to their own devices to make sense of the situation. We want to first assess how the child made sense of the situation.

|

Sample Script:

“Hey, is it okay for us to talk about what happened earlier at the grocery store? How did this situation make you feel? Unfortunately, these situations happen to all kinds of people, not just Asian Americans. What is happening is that people are sometimes taught to fear and dislike what is different or unknown. But this is not a reflection on you or our people. This reflects that racism is still very prevalent and is something we need to be aware of when we are outside of our home. What did you think about how we responded? Did you think it was helpful?” |

Give the child space to acknowledge their emotions and process how they understood this situation. Once the child has shared their reflections and is emotionally calm, then we can move forward on how to help the child understand the different possible perspectives of the situation. Be curious and brainstorm with your child about why someone might say this to the grandfather and family friend. If the child is old enough, you can share about the term “xenophobia” and how Asian Americans have been feared throughout history simply because we are viewed as different, or foreign.

STEP 3: PROBLEM-SOLVING

Encourage your child to consider:

Brainstorm ideas freely with your child before beginning to narrow down on the options that make the most sense and protect your family’s safety, dignity, and freedom. Bystander intervention is an important topic to discuss when racialized incidents arise in public spaces. You can learn more about bystander intervention and keeping safe in public spaces using the following guide: immigranthistory.org/bystander

Encourage your child to consider:

- How can we change how we respond the next time this type of situation happens?

- What ideas might you have for how we could handle this situation differently?

Brainstorm ideas freely with your child before beginning to narrow down on the options that make the most sense and protect your family’s safety, dignity, and freedom. Bystander intervention is an important topic to discuss when racialized incidents arise in public spaces. You can learn more about bystander intervention and keeping safe in public spaces using the following guide: immigranthistory.org/bystander

STEP 4: PRACTICE

Practice the options you and your child have decided on and try out what feels most suitable for your family.

Practice the options you and your child have decided on and try out what feels most suitable for your family.

Hypothetical Scenario #3: When Your Child Makes a Biased Statement

Your child is in elementary school. He tells you, "I don't like Max," and when you ask him why, he responds, "because he has black skin."

STEPS 1 + 2: EMOTIONAL & PHYSICAL REGULATION + INVESTIGATION

Take some time to check in with your child’s emotions before moving on, even if your first instinct is to directly address your child’s statement. Is your child still angry or upset? Give them time to process these heightened emotions. If necessary, try some grounding activities such as deep breathing, playing music, or drawing.

It is important that we do not react with shame and blame after hearing our child say these words. Don't start off with: "You can't say that! That's racist!" Instead, you can turn this into a teachable moment and become curious first to what prompted that statement. We want to encourage our children to share openly with us. If we start with blame, it will cause our children to shut down and become defensive. Instead, we can remain open and become a detective about why our child said these words.

Take some time to check in with your child’s emotions before moving on, even if your first instinct is to directly address your child’s statement. Is your child still angry or upset? Give them time to process these heightened emotions. If necessary, try some grounding activities such as deep breathing, playing music, or drawing.

It is important that we do not react with shame and blame after hearing our child say these words. Don't start off with: "You can't say that! That's racist!" Instead, you can turn this into a teachable moment and become curious first to what prompted that statement. We want to encourage our children to share openly with us. If we start with blame, it will cause our children to shut down and become defensive. Instead, we can remain open and become a detective about why our child said these words.

STEPS 3 + 4: PROBLEM-SOLVING + PRACTICE

While you do not want to shame your child, you still need to help your child understand why this statement is wrong and hurtful. Resist any urges to disregard the statement, even if your child tells you during the Investigation stage that Max has done something very hurtful. You can begin the empathy-building process at this step, where you can invoke family values and state what you believe. You can help your child build a sense of empathy and begin taking perspectives outside of their own view.

In addition to addressing this specific incident, you may consider incorporating more books and stories that focus on Black history and the experiences of African Americans. There are also children's books that use an anti-racist approach to talk about race, ethnicity and heritage. Visit the Resources section for some helpful links.

While you do not want to shame your child, you still need to help your child understand why this statement is wrong and hurtful. Resist any urges to disregard the statement, even if your child tells you during the Investigation stage that Max has done something very hurtful. You can begin the empathy-building process at this step, where you can invoke family values and state what you believe. You can help your child build a sense of empathy and begin taking perspectives outside of their own view.

In addition to addressing this specific incident, you may consider incorporating more books and stories that focus on Black history and the experiences of African Americans. There are also children's books that use an anti-racist approach to talk about race, ethnicity and heritage. Visit the Resources section for some helpful links.

|

Sample Script:

“Would it be fair if someone did not like you because of the color of your skin? How would that make you feel? You can disagree with Max’s behaviors, but it is not fair to label Max as a bad person. Everyone can make mistakes or hurt other people, including yourself. Can you remember a time when someone judged you based on one part of you instead of taking the time to get to know you?” |

Our children spend so much of their time at school and under the care of educators for a majority of their day. It is important to try to build a relationship with the educators and the school early in the academic year so that families and caregivers can work in partnership with the school to support our children.

When the first or only time you contact a teacher or school is around a negative incident and vice versa, it’s much harder to have an open conversation about the best way to support your child. Your children should also know that there are support services and adults in the school building that can help. This is still true for older students who may be able to advocate for themselves; in building relationships with their teachers and other school staff, they will know whom to approach for help if needed.

Districts may have different names for these positions, or may not have all these various administrators and support staff. In general, your first line of contact is usually the classroom teacher for the elementary school or any trusted adult, and at the secondary level, any trusted adult such as a subject area teacher, school counselor or any member of a student support team, will be able to lead you to the right resources. If issues are not resolved at the teacher level or other school student support staff, contact the principal.

Below are suggestions for people to contact in different situations that may arise for you or your children.

When the first or only time you contact a teacher or school is around a negative incident and vice versa, it’s much harder to have an open conversation about the best way to support your child. Your children should also know that there are support services and adults in the school building that can help. This is still true for older students who may be able to advocate for themselves; in building relationships with their teachers and other school staff, they will know whom to approach for help if needed.

Districts may have different names for these positions, or may not have all these various administrators and support staff. In general, your first line of contact is usually the classroom teacher for the elementary school or any trusted adult, and at the secondary level, any trusted adult such as a subject area teacher, school counselor or any member of a student support team, will be able to lead you to the right resources. If issues are not resolved at the teacher level or other school student support staff, contact the principal.

Below are suggestions for people to contact in different situations that may arise for you or your children.

Situation |

Contact |

General classroom and subject area content questions |

|

General school-related questions (events, use of technology, school related website accounts, school lunch, special programs, etc.) |

|

If you need a language interpreter for a meeting or materials translated |

|

When you need to communicate a medical or mental health related situation |

|

When your child has experienced a racial incident, verbal or physical harassment |

|

When your child has experienced bullying defined as:

|

|

Email Templates

You can access editable versions of these email templates (in English) in Google Docs here!

TEMPLATE 1: INTRODUCING YOUR CHILD AND YOURSELF TO THE TEACHER AT THE START OF THE YEAR

Email Template |

Sample Email |

Subject line: Introducing [your child’s name] Dear Ms./Mr./Dr. ______________, My name is ______ and I am [Child’s Name]’s [relationship: parent, aunt, uncle, guardian, etc.]. We are excited to be a part of your classroom this year. As we start the new year, I wanted to share a little about [Child’s Name]. [Child’s Name] enjoys [list a few things that your child enjoys doing, hobbies, and activities], and likes to learn about [list any subjects that your child is interested in]. She/he has many strengths as well, and is [list strengths]. In the past, our child has needed some help in [list topics/areas/tasks] and has benefitted from supports like [supports] to help her/him grow as a student and an individual. The best way to contact me is by [phone/text/email] at [phone number/email address]. The best times to reach me are [days, times of day: morning, afternoon, evenings]. What is the best way to contact you throughout the school year and what is the best way to get help outside of school hours? Thank you in advance for your time. We look forward to a good school year. Sincerely, [Your name] |

Subject line: Introducing Tony Dear Ms./Mr./Dr. ______________, My name is Meihua Zhang and I am Tony’s aunt and caregiver. We are excited to be a part of your classroom this year. As we start the new year, I wanted to share a little about Tony. He enjoys reading, creating art, playing soccer, and likes to learn about current events. He has many strengths as well, and is independent, organized, and thoughtful. In the past, Tony has needed some help in adjusting to new situations and has benefitted from supports like having a consistent schedule, clear expectations, and building a trusting relationship with an adult at the school to help him grow as a student and an individual. The best way to contact me is by text message at 860-XXX-XXXX. The best times to reach me are Monday before noon and Thursdays between 11:00am and 2:00pm. What is the best way to contact you throughout the school year and what is the best way to get help outside of school hours? Thank you in advance for your time. We look forward to a good school year. Sincerely, Meihua Zhang |

TEMPLATE 2: REQUESTING A LANGUAGE INTERPRETER (SPOKEN) OR TRANSLATION OF MATERIALS (WRITTEN)

Email Template |

Sample Email |

Subject line: Request for translated materials and interpretation Dear Ms./Mr./Dr. ________________, My name is ______ and I am [Child’s Name]’s [relationship: parent, aunt, uncle, guardian, etc.]. I speak [language] and would like to have school materials in my home language so I can support my child at home. I would also like to know what interpreter options are available. Thank you in advance for your time. I look forward to learning more about school activities and initiatives and ways that I can continue to support my child. Sincerely, [Your name] |

Subject line: Request for translated materials and interpretation Dear Ms./Mr./Dr. ________________, My name is Yuri Tanaka and I am Maya’s parent. I speak Japanese and would like to have school materials in my home language so I can support my child at home. I would also like to know what interpreter options are available. Thank you in advance for your time. I look forward to learning more about school activities and initiatives and ways that I can continue to support my child. Sincerely, Yuri Tanaka |

TEMPLATE 3: CONTACTING SCHOOL COUNSELOR/SOCIAL WORKER ABOUT CHILD'S MENTAL HEALTH

Email Template |

Sample Email |

Subject line: Request for meeting Dear Ms./Mr./Dr. ________________, My name is ______ and I am [Child’s Name]’s [relationship: parent, aunt, uncle, guardian, etc.]. I would like to speak with you because I am worried about my child's mental health. I would like to learn about what services the school can provide to help my child. The best way to contact me is by [phone/text/email] at [phone number/email address]. The best times to reach me are [days, times of day: morning, afternoon, evenings]. Thank you for your time. I look forward to hearing from you. Sincerely, [Your Name] |

Subject line: Request for meeting Dear Ms./Mr./Dr. ________________, My name is Andy Tran and I am Derek’s father. I would like to speak with you because I am worried about Derek’s mental health. I would like to learn about what services the school can provide to help my child. The best way to contact me is by email at [email protected]. The best times to reach me are Monday mornings or Wednesdays after 3pm. Thank you for your time. I look forward to hearing from you. Sincerely, Andy Tran |

TEMPLATE 4: CONTACTING TEACHER/ADVISOR/SCHOOL COUNSELOR ABOUT BULLYING INCIDENT

Email Template |

Sample Email |

Subject line: Concern about bullying Dear Ms./Mr./Dr. ________________, My name is ______ and I am [Child’s Name]’s [relationship: parent, aunt, uncle, guardian, etc.]. [Child's Name] has been bullied at school and I am requesting [action you would like school to take]. The bullying incident(s) occurred on [date(s) and time(s), be as specific as possible]. The bullying involved [bullying student's information, including name & grade], who [describe how they bullied your child]. As a result of these incidents, [list the negative effects on your child]. I am requesting a meeting with you [list specific time frame] to discuss next steps and interventions to ensure that this bullying will stop. I am attaching the "incident sheet" [see below for template] so that the school can interview witnesses and others involved as you investigate the bullying incident. Once a thorough investigation has been done, please provide the full and final report for us to see. School is supposed to be a safe space for all students and it’s the school’s responsibility to provide an environment where everyone can thrive, including [Child's name]. The best way to contact me is by [phone/text/email] at [phone number/email address]. [If desired: Please keep this information confidential until our meeting.] Best, [Your Name] |

Subject line: Concern about bullying Dear Ms./Mr./Dr. ________________, My name is Kris Bui and I am Sam’s guardian. Sam has been bullied at school and I am requesting an investigation and a prompt response from the school district to ensure that it will stop. The bullying incidents occurred on 10/4, 10/11, and 10/29 immediately after school as they transitioned to the bus in the library hallway. The bullying involved 10th graders (name of student) and (name of student) who repeatedly slammed Sam into the lockers while a 9th grader (name of student) threw Sam’s phone on the ground. (name of student) and (name of student) witnessed the incidents, and the 11th grade English teacher was finally able to disrupt the incident enough for other teachers to help. As a result of these incidents, he has missed school due to stress related stomach issues and is refusing to go back to school. I am requesting a meeting with you this week to discuss next steps and interventions to ensure that this bullying will stop. I am attaching the “incident sheet” so that the school can interview witnesses and others involved as you investigate the bullying incident. Once a thorough investigation has been done, please provide the full and final report for us to see. School is supposed to be a safe space for all students and it’s the school’s responsibility to provide an environment where everyone can thrive, including Sam. The best way to contact me is by email ([email protected]) or phone call at 860-XXX-XXXX. Best, Kris Bui |

INCIDENT SHEET TEMPLATE

Create a separate incident sheet for each incident. Download the template on Google Docs here.

Date/Time of Incident |

Fill in |

Children Involved |

Fill in, including bystanders |

Location of Incident |

E.g., playground, cafeteria, hallway, online |

Type of Incident |

E.g., physical, verbal, online |

Form of Harassment |

E.g., racist, religious, cultural, sexual, disability, gender, LGBTQ, home circumstances, socioeconomic class |

Brief Summary of Incident & Impact on Child |

Fill in and take photos of any injuries, or screenshots of online incidents |

Statements from Witnesses/Bystanders |

Fill in |

School Staff to Whom Incident Was Reported |

Fill in and keep all records of communication |

Agreed Upon Action Taken by School |

Fill in |

Follow-Up Communication or Action with School |

Fill in |

Talking to Kids about Race:

"Bullying & Bias," Learning for Justice (https://www.learningforjustice.org/topics/bullying-bias?gclid=CjwKCAjwg4-EBhBwEiwAzYAlsm-nKZvmH-CifnIUBSbkcYKdOGFcOukApRrqMY_TpwQEfHJLIrax1hoC4KUQAvD_BwE)

"How to Resolve Racially Stressful Situations," Howard C. Stevenson, TedTalk (https://www.ted.com/talks/howard_c_stevenson_how_to_resolve_racially_stressful_situations?language=en)

Resmaa Menakem, My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies (Book)

"Our Black History Month Reading List for Asian Americans," 18 Million Rising (https://18millionrising.org/2020/02/bhm_reads.html).

"How to Talk to Your Kids About Anti-Racism: A List of Resources," PBS (https://www.pbssocal.org/education/how-to-talk-to-your-kids-about-anti-racism-a-list-of-resources)

Howard C. Stevenson, Promoting Racial Literacy in Schools: Differences that Make a Difference (Book)

"Storytelling for Social Justice," Lee Anne Bell, Harvard Educational Review (https://www.hepg.org/her-home/issues/harvard-educational-review-volume-81-number-2/herbooknote/storytelling-for-social-justice_363)

Asian American History:

Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America (Book)

Shelley Sang-Hee Lee, A New History of Asian America (Book)

PBS, Asian Americans (film series), (www.pbs.org/weta/asian-americans/)

Lesson plans based on the PBS series (pbslearningmedia.org/collection/asian-americans-pbs/)

IH's lesson plans on Asian American History (www.immigranthistory.org/lessonplans.html)

"Bullying & Bias," Learning for Justice (https://www.learningforjustice.org/topics/bullying-bias?gclid=CjwKCAjwg4-EBhBwEiwAzYAlsm-nKZvmH-CifnIUBSbkcYKdOGFcOukApRrqMY_TpwQEfHJLIrax1hoC4KUQAvD_BwE)

"How to Resolve Racially Stressful Situations," Howard C. Stevenson, TedTalk (https://www.ted.com/talks/howard_c_stevenson_how_to_resolve_racially_stressful_situations?language=en)

Resmaa Menakem, My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies (Book)

"Our Black History Month Reading List for Asian Americans," 18 Million Rising (https://18millionrising.org/2020/02/bhm_reads.html).

"How to Talk to Your Kids About Anti-Racism: A List of Resources," PBS (https://www.pbssocal.org/education/how-to-talk-to-your-kids-about-anti-racism-a-list-of-resources)

Howard C. Stevenson, Promoting Racial Literacy in Schools: Differences that Make a Difference (Book)

"Storytelling for Social Justice," Lee Anne Bell, Harvard Educational Review (https://www.hepg.org/her-home/issues/harvard-educational-review-volume-81-number-2/herbooknote/storytelling-for-social-justice_363)

Asian American History:

Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America (Book)

Shelley Sang-Hee Lee, A New History of Asian America (Book)

PBS, Asian Americans (film series), (www.pbs.org/weta/asian-americans/)

Lesson plans based on the PBS series (pbslearningmedia.org/collection/asian-americans-pbs/)

IH's lesson plans on Asian American History (www.immigranthistory.org/lessonplans.html)